APP Editors’ Note: Wolfram Eilenberger is a philosopher, journalist, and writer. His passion is the application of philosophical ideas to our life today, whether it be in politics, culture or sport. He is the editor of Philosophie Magazin, and in high demand as a German intellectual, often appearing on talk shows. He has published eight books, including the best-selling novel Finnen von Sinnen which has been translated into several languages. He has taught at the University of Toronto (Canada), Indiana University (Bloomington, USA) and University of Arts, Berlin. And since 2017 he has been program director of the Berlin publishing house Nicolai Publishing & Intelligence. His book Time of the Magicians: The Great Decade of Philosophy 1919-1929 (Klett-Cotta) was published in March 2018. More information about his work can be found HERE.

The original version of the following article appeared in Die Zeit on 28 February 2018, HERE.

The APP version is a quick-&-dirty, free-wheeling, and magical translation by Mr Nemo.

In any case, the parallels between the sorry state of contemporary German philosophy and the sorry state of contemporary Anglo-American philosophy are, well, obvious.

Anyone who talks to German philosophy professors about the current state of their discipline looks into sad eyes. Perplexity mingles with shame and frustration about “the whole enterprise,” with a cultural pessimism that has always been typical in this country. It is indisputable: The last philosophical hurrahs happened at least 50 years ago. And there is no one in sight who is comparable in status, power of thought and global presence with today’s Grand Old Men of that era. (Jürgen Habermas: 88 years old, Dieter Henrich: 91 years old, Robert Spaemann: 90 years old, Kurt Flasch: 87 years old –even the eternal enfant terrible Peter Sloterdijk has now exceeded 70)

There is currently no question whatsoever of any international or even any interdisciplinary appeal of German philosophy.

How could this happen in the land of Leibniz and Kant, Hegel and Schopenhauer, Nietzsche and Arendt? Especially at a time when the public interest in philosophical reflection is exploding and successfully establishing itself on the open market as a result of a huge repertoire of media formats? Philosophical monthly magazines such as Hohe Luft or Philosophy Magazin (of which I am the former editor-in-chief) reach a circulation of 60,000 copies; festivals like phil.cologne attract more than 10,000 people over the course of a week. And the non-fiction bestseller lists have been dominated by popular philosophy for years.

Moreover, one may blame our present world for many things, but not that it does not give rise to big and serious questions: digitalisation is revolutionizing the space of discourse; genetic engineering intervenes in the foundations of creation; artificial intelligence delves deep into our self-image; climate change calls for global rethinking; and economics and physics are in a serious foundational crisis while the knowledge of the vastness and riches of the universe explodes in ways that make our position in the cosmos questionable again. The world is on the move, and the original Kantian question “What is the human being?” is more urgent than ever. Academic philosophy, on the other hand, stagnates in an increasingly irrelevant self-reflection on its own traditional insider-connections. Why?

Boring excellence

The current situation is paradoxical. Never in history has there been such a multitude of academically well-educated philosophers as in 2018. So if quantity necessarily changes to quality at some point, the next big system breakthrough should only be a matter of weeks. Especially since the level of knowledge and diversity of the younger people, still struggling for their academic-career breakthroughs, at first glance looks almost breathtaking.

In all likelihood, not one of the groundbreaking articles in moral philosophy from the 1960s and 1970s by such thinkers as Philippa Foot or Bernard Williams, would have the slightest chance of being accepted by one of the leading journals today. It would be just as unlikely for Günter Netzer or Wolfgang Overath to make the starting line-up today at Hannover 96–or for Jimmy Connors to survive the second round in a Grand Slam tournament.

Professional academic philosophers are all well-trained, extremely career-oriented, and can do philosophically exactly what the ARD football expert Mehmet Scholl, in a controversial statement about the new generation of football professionals and Bundesliga coaches, proposed: namely, that they could, if necessary, even while asleep, “fart upside-down 18 times in unison.”

Moreover, and here too, the analogy to professional sports is perfect, for it is not worth the effort either watching pro sports or reading anyone in contemporary German professional philosophy. Nothing ever happens “out there in TV land” that would really interest any waking mind, let alone fascinate or even productively confuse anyone. If one takes a synoptic view, it is clear that the low level of inherent significance that is currently prevalent in German philosophy is above all a sign of hopelessly exhausted research programs and questions.

The average number of readers per published philosophy article: two or three

A professor teaching abroad, who for many years edited one of the world’s most important journals of Analytic philosophy, without irony, estimated the average number of readers of the articles published there at two or three people. The leading philosophy journals have thus alienated themselves from everything that could ever constitute living and reality-saturated thinking.

What is being discussed there–almost exclusively in English–literally does not interest anyone. Neither outside the profession, nor inside the profession. Yes, it does not even interest the authors themselves, who, during the potentially most creative phases of their thinking lives, usually without any relevant extra-academic professional experience, launch pre-formatted discussions in pre-formatted language into absolute nothingness. In the rare cases of success, at age 40 they begin to acquire a W2 reputation and henceforth to teach and “do research,” for a salary that differs only slightly from the salary of a senior research assistant.

Indeed, science is a cruel lover! In the face of such prospects, who could ever find the energy to wonder whether philosophy is or should be a science in the first place?

The pressure of the rankings

It is precisely the normative model of science-envy that, in the form of the evaluation methods that are forcibly imposed in the natural sciences, makes the desert of our [contemporary German] thinking grow a little bigger each day. Given the yearly several dozen articles cranked out by the average economist or biologist, even nimble philosophical fingers cannot keep up. The logic of global rankings is currently going expanding like the net of a fishing trawler across the coral reef. In the meantime, at some universities free-standing philosophical monographs–as opposed to specialized articles– are no longer recognized as relevant research achievements. They are not even included in the annual evaluation reports.

Since resistance to this rankings-terrorism is futile, professional philosophy surrenders to these institutional illusory necessities, and then commits suicide for fear of dying. The show must go on! And to what end? To quasi-corporately guide another year of well-examined and absolutely frustrated young researchers through the system. German philosophy lacks everything but state funding.

But remember: Ludwig Wittgenstein – author of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus – published a single article within the framework of his own way of philosophical thinking. On the day he was supposed to read it publicly at a conference, this seemed so worthless to him, that he spontaneously changed the subject and instead free-associated on the problem of infinity. It was his sole act of participation in any such event.

From consensus to conformism

The overwhelming will-to-quiet-conformism may itself have philosophical reasons. Those who believe that philosophizing is about connecting theses rather than about providing true insights, about discursive exchange rather than revolutions in thinking, about consensus rather than creative disagreement, will find it much easier to establish themselves as philosophers according to the logic of public funding.

In this context, it is a particular misconception that the final representatives of the Frankfurt School, as well as post-structuralism (in the wake of Foucault and Derrida), have permanently secured their “place in the sun” by being “systematically critical” at all times, as a self-styled minority. In fact, they have become hegemonic, and it is precisely these two traditional networks which, with a puritanical sense of cleanliness, take care to avoid seeing that the broad space of thought can be fundamentally changed by new ideas.

One-third bureaucracy, one-third teaching, one-third third-party funding: without magic

What can be said in a positive way about these lines of thinking, in comparison to Analytic philosophy, which is deeply folded in upon itself, is that at least they are in marginal contact with other university subjects. There is still something interdisciplinary that can conjure up something “exciting” and thus qualify it as a “cluster of excellence.”

In any case, Walter Benjamin would have desperately shaken his head at the belief that truth is a matter of consensus, that language is primarily a means of communication, and that ethics is primarily a matter of discourse. So too would Martin Heidegger, Wittgenstein, or even Ernst Cassirer, the last four great figures who knew how to get philosophical things rolling in the German-speeaking world. Within a single magical decade, from 1919 to 1929, all the relevant traditions of contemporary philosophy—logico-linguistic analysis, existentialism, hermeneutics, deconstruction, critical theory, and cultural semiotics – received their decisive baptismal impulses. Since then, so for a full century, we can frankly say, in Germany philosophical thinking has been administered academically, diversified in an exemplary way, and not infrequently also strategically sedated.

The few living beings who claim to speak with their own philosophical voice have been fleeing to the art schools for decades, in order to put themselves at one or two removes from the well-policed borders of the professional academy. This is a good strategy. But even inside professional academic philosophy, one hears more and more frequently of cases of those who have voluntarily withdrawn themselves altogether from The Ministry of Thought, and quit. Who can blame them? It’s nothing but one-third bureaucracy, one-third teaching apprenticeship, one-third third-party funding.

A mirror held up to the discipline

Just so that I make myself clear: This rant is not primarily about a neo-romantic longing for new philosophers, or for hitherto unknown new levels of philosophical argument, and certainly not about malice, but simply about possible ways out of the prevailing state of listless total stagnation. And of course, such a direct attack on “the profession” and on “professional academic philosophical thinking” is somewhat unfair, and undifferentiated as to the attribution of culpability. But that does not change the one truth about which, as far as I can see, all players on the field are in agreement: German philosophy is currently experiencing its historically weakest moment. Given this certainty, professional academic philosophers are leading lives of quiet desperation.

And yet, the mature courage to endure this thoroughly disappointing mirror-reflection of itself, and at the same time to grasp it as an imperative to philosophize anew, is all it ever took to lead philosophical thinking down a new path. It’s high time to do something about it.

![]()

Against Professional Philosophy is a sub-project of the online mega-project Philosophy Without Borders, which is home-based on Patreon here.

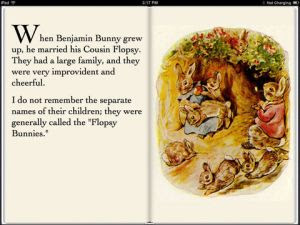

Please consider becoming a patron! We’re improvident, but cheerful.