In “Let’s Make More Movies,” the epistemological anarchist Paul Feyerabend wrote this:

The separation of subjects that is such a pronounced characteristic of modern philosophy is … not altogether undesirable. It is a step on the way to a more satisfactory type of myth. What is needed to proceed further is not the return to harmony and stability as too many critics of the status quo, Marxists included, seem to think, but a form of life in which the constituents of older myths —theories, books, images, emotions, sounds, institutions — enter as interacting but antagonistic elements. Brecht’s theatre was an attempt to create such a form of life. He did not entirely succeed. I suggest we try movies instead. (P. Feyerabend, “Let’s Make more Movies,” in The Owl of Minerva: Philosophers on Philosophy, Ch. J. Bontempo and S. J. Odell (eds), McGraw-Hill: New York 1975, pp. 201-210.)

INTRODUCTION

I am vividly struck, and deeply dismayed, by many significant sociocultural, political, and philosophical parallels between the 1920s and the 2010s.

Then, in the USA, Britain, and Central/Western Europe, unconstrained, exploitative capitalism, philosophical scientism and mechanism, and the absurdity of human existence in a world that’s horrendously rich and playing itself out with pleasure-seeking at the top, professionals and small-time capitalists, all solidly, stolidly, and blindly bourgeois, in the middle, a fully exploited working class just below that, and the horrendously poor and suffering at the bottom.

Now, thanks to runaway industrial, military, and information technology, thanks to the USA-driven neoliberalization of the world economy, and thanks to worldwide environmental exploitation, warming, and impending eco-disaster, it’s all gone global.

Apparently, the percentage of the world’s population “living in extreme poverty” has dropped to less than 10%.

But however they measure “extreme poverty,” that’s not the fucking point.

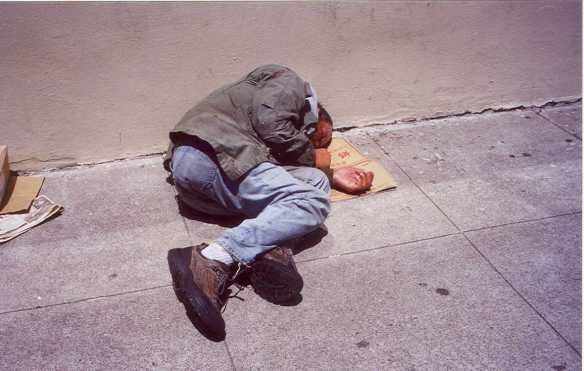

The fucking point is, how many people don’t have enough to meet the minimal requirements of respect for human dignity?

Meeting the minimal requirements means: having enough food, enough decent housing, enough health care, enough access to healthy environments, enough access to intellectually liberating education, enough surplus income for enjoying one’s life, and enough freedom from the threat of being arbitrarily coerced.

How many people are living and dying below this line? 50% of humanity? 60%? Significantly more than that? Anyhow, the majority of humanity. Let’s call them the oppressed.

Marx obsessed about “the proletariat,” the exploited working class in capitalized countries, but instead he should have obsessed about the oppressed.

The existence of any oppressed people anywhere is a moral scandal, whether in the 1920s or the 2010s.

In any case, the accumulation of horrendous wealth by the top 1% of capitalist bosses has increased to close to 40%.

And professionalization is swallowing up the middle, careening forward into the future in an ideological night of the living dead. In 1920, only 5% of the workforce were professionals. In the USA today, it’s roughly 20%, and growing rapidly.

Of course, in between the 1920s and the 2010s, the following big things happened: the rise of German and Italian fascism, and Japanese militarism, in the 1930s; World War II, and the defeat of Germany, Japan, and Italy, in the 1940s; the emergence of the USA as a political super-power, together with Eastern European political domination by Soviet Communism, and the rise of Asian communism, in wake of the War in the late 1940s and 1950s; American cultural and political competition with Soviet and Chinese communism, and the Cold War, from the 1960s through the 1980s; the fall of Soviet communism in the 1980s; and the almost-complete worldwide economic and cultural domination by the USA, via global corporate capitalism, in the void left by the fall of Soviet communism, since then, in the 90s and into the 2000s, alongside some serious side-conflicts with Islamic fundamentalists.

But now thinking non-diachronically, what are the deep conceptual connections between the 20s and the 10s?

Let’s see….

1. THE SCIENTIFIC CONCEPTION OF THE WORLD: THE VIENNA CIRCLE, 1929

Hans Hahn, Otto Neurath, Rudolf Carnap

The modern scientific world-conception has developed from work on the problems just mentioned. We have seen how in physics, the endeavours to gain tangible results, at first even with inadequate or still insufficiently clarified scientific tools, found itself forced more and more into methodological investigations. Out of this developed the method of forming hypotheses and, further, the axiomatic method and logical analysis; thereby concept formation gained greater clarity and strength. The same methodological problems were met also in the development of foundations research in physical geometry, mathematical geometry and arithmetic, as we have seen. It is mainly from all these sources that the problems arise with which representatives of the scientific world-conception particularly concern themselves at present. Of course it is still clearly noticeable from which of the various problem areas the individual members of the Vienna Circle come. This often results in differences in lines of interests and points of view, which in turn lead to differences in conception. But it is characteristic that an endeavour toward precise formulation, application of an exact logical language and symbolism, and accurate differentiation between the theoretical content of a thesis and its mere attendant notions, diminish the separation. Step by step the common fund of conceptions is increased, forming the nucleus of a scientific world-conception around which the outer layers gather with stronger subjective divergence.

Looking back we now see clearly what is the essence of the new scientific world-conception in contrast with traditional philosophy. No special ‘philosophic assertions’ are established, assertions are merely clarified; and at that assertions of empirical science, as we have seen when we discussed the various problem areas. Some representatives of the scientific world-conception no longer want to use the term ‘philosophy’ for their work at all, so as to emphasise the contrast with the philosophy of (metaphysical) systems even more strongly. Whichever term may be used to describe such investigations, this much is certain: there is no such thing as philosophy as a basic or universal science alongside or above the various fields of the one empirical science; there is no way to genuine knowledge other than the way of experience; there is no realm of ideas that stands over or beyond experience. Nevertheless the work of ‘philosophic’ or ‘foundational’ investigations remains important in accord with the scientific world-conception. For the logical clarification of scientific concepts, statements and methods liberates one from inhibiting prejudices. Logical and epistemological analysis does not wish to set barriers to scientific enquiry; on the contrary, analysis provides science with as complete a range of formal possibilities as is possible, from which to select what best fits each empirical finding (example: non-Euclidean geometries and the theory of relativity).

The representatives of the scientific world-conception resolutely stand on the ground of simple human experience. They confidently approach the task of removing the metaphysical and theological debris of millennia. Or, as some have it: returning, after a metaphysical interlude, to a unified picture of this world which had, in a sense, been at the basis of magical beliefs, free from theology, in the earliest times.

The increase of metaphysical and theologizing leanings which shows itself today in many associations and sects, in books and journals, in talks and university lectures, seems to be based on the fierce social and economic struggles of the present: one group of combatants, holding fast to traditional social forms, cultivates traditional attitudes of metaphysics and theology whose content has long since been superseded; while the other group, especially in central Europe, faces modern times, rejects these views and takes its stand on the ground of empirical science. This development is connected with that of the modern process of production, which is becoming ever more rigorously mechanised and leaves ever less room for metaphysical ideas. It is also connected with the disappointment of broad masses of people with the attitude of those who preach traditional metaphysical and theological doctrine. So it is that in many countries the masses now reject these doctrines much more consciously than ever before, and along with their socialist attitudes tend to lean towards a down-to-earth empiricist view. In previous times, materialism was the expression of this view; meanwhile, however, modern empiricism has shed a number of inadequacies and has taken a strong shape in the scientific world-conception.

Thus, the scientific world-conception is close to the life of the present. Certainly it is threatened with hard struggles and hostility. Nevertheless there are many who do not despair but, in view of the present sociological situation, look forward with hope to the course of events to come. Of course not every single adherent of the scientific world-conception will be a fighter. Some, glad of solitude, will lead a withdrawn existence on the icy slopes of logic; some may even disdain mingling with the masses and regret the ‘trivialized’ form that these matters inevitably take on spreading. However, their achievements too will take a place among the historic developments. We witness the spirit of the scientific world-conception penetrating in growing measure the forms of personal and public life, in education, upbringing, architecture, and the shaping of economic and social life according to rational principles. The scientific world-conception serves life, and life receives it.

Members of the Vienna Circle:

Gustav Bergmann

Rudolf Carnap

Herbert Feigl

Philipp Frank

Kurt Gödel

Hans Hahn

Viktor Kraft

Karl Menger

Marcel Natkin

Otto Neurath

Olga Hahn-Neurath

Theodor Radakovic

Moritz Schlick

Friedrich Waismann

2. THE HOLLOW MEN, 1925

T. S. Eliot

Mistah Kurtz—he dead.

A penny for the Old Guy

I

We are the hollow men

We are the stuffed men

Leaning together

Headpiece filled with straw. Alas! Our dried voices, when

Our dried voices, when

We whisper together

Are quiet and meaningless

As wind in dry grass

Or rats’ feet over broken glass

In our dry cellar

Shape without form, shade without colour,

Paralysed force, gesture without motion;

Those who have crossed

With direct eyes, to death’s other Kingdom

Remember us—if at all—not as lost

Violent souls, but only

As the hollow men

The stuffed men.

II

Eyes I dare not meet in dreams

In death’s dream kingdom

These do not appear:

There, the eyes are

Sunlight on a broken column

There, is a tree swinging

And voices are

In the wind’s singing

More distant and more solemn

Than a fading star.

Let me be no nearer

In death’s dream kingdom

Let me also wear

Such deliberate disguises

Rat’s coat, crowskin, crossed staves

In a field

Behaving as the wind behaves

No nearer—

Not that final meeting

In the twilight kingdom

III

This is the dead land

This is cactus land

Here the stone images

Are raised, here they receive

The supplication of a dead man’s hand

Under the twinkle of a fading star.

Is it like this

In death’s other kingdom

Waking alone

At the hour when we are

Trembling with tenderness

Lips that would kiss

Form prayers to broken stone.

IV

The eyes are not here

There are no eyes here

In this valley of dying stars

In this hollow valley

This broken jaw of our lost kingdoms

In this last of meeting places

We grope together

And avoid speech

Gathered on this beach of the tumid river

Sightless, unless

The eyes reappear

As the perpetual star

Multifoliate rose

Of death’s twilight kingdom

The hope only

Of empty men.

V

Here we go round the prickly pear

Prickly pear prickly pear

Here we go round the prickly pear

At five o’clock in the morning.

Between the idea

And the reality

Between the motion

And the act

Falls the Shadow

For Thine is the Kingdom

Between the conception

And the creation

Between the emotion

And the response

Falls the Shadow

Life is very long

Between the desire

And the spasm

Between the potency

And the existence

Between the essence

And the descent

Falls the Shadow

For Thine is the Kingdom

For Thine is

Life is

For Thine is the

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.

3. THE MALTESE FALCON, 1929

Dashiell Hammett

Spade sat down in the armchair beside the table and without any preliminary, without an introductory remark of any sort, began to tell the girl about a thing that had happened some years before in the Northwest. He talked in a steady matter-of-fact voice that was devoid of emphasis or pauses, though now and then he repeated a sentence slightly rearranged, as if it were important that each detail be related exactly as it had happened.

At the beginning Brigid O’Shaughnessy listened with only partial attentiveness, obviously more surprised by his telling the story than interested in it, her curiousity more engaged with his purpose in telling the story than with the story he told; but presently, as the story went on, it caught her more and more fully and she became still and receptive.

A man named Flitcraft had left his real-estate-office, in Tacoma, to go to luncheon one day and had never returned. He did not keep an engagement to play golf after four that afternoon, though he had taken the initiative in making the engagement less than half and hour before he went out to luncheon. His wife and children never saw him again. His wife and he were supposed to be on the best of terms. He had two children, boys, one five and the other three. He owned his house in a Tacoma suburb, a new Packard, and the rest of the appurtenances of successful American living.

Flitcraft had inherited seventy thousand dollars from his father, and, with his success in real estate, was worth something in the neighbourhood of two hundred thousand dollars at the time he vanished. His affairs were in order, though there were enough loose ends to indicate that he had not been setting them in order preparatory to vanishing. A deal that would have brought him an attractive profit, for instance, was to have been concluded the day after the one on which he disappeared. There was nothing to suggest that he had more than fifty or sixty dollars in his immediate possession at the time of his going. His habits for months past could be accounted for too thoroughly to justify any suspicion of secret vices, or even of another woman in his life, though either was barely possible.

“He went like that,” Spade said, “like a fist when you open your hand”….

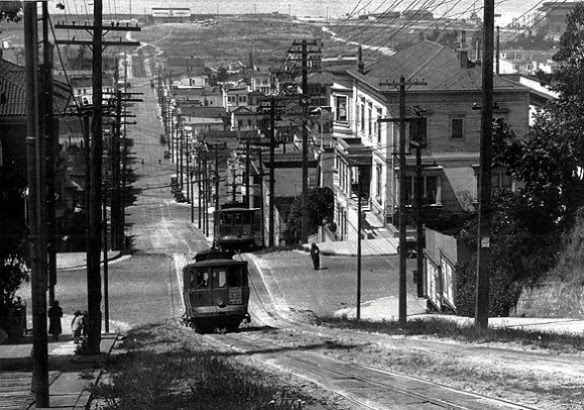

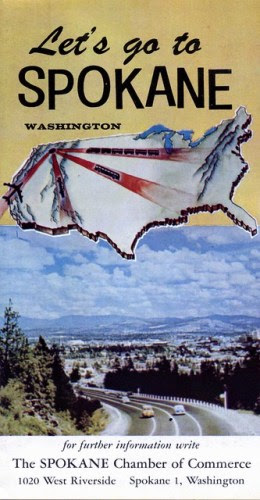

“… Well, that was in 1922. In 1927 I was with one of the big detective agencies in Seattle. Mrs. Flitcraft came in and told us somebody had seen a man in Spokane who looked a lot like her husband. I went over there. It was Flitcraft, all right. He had been living in Spokane for a couple of years as Charles – that was his first name – Pierce. He had a automobile-business that was netting him twenty or twenty-five thousand a year, a wife, a baby son, owned his home in a Spokane suburb, and usually got away to play golf after four in the afternoon during the season.”

Spade had not been told very definitely what to do when he found Flitcraft. They talked in Spade’s room at the Davenport. Flitcraft had no feeling of guilt. He had left his first family well provided for, and what he had done seemed to him perfectly reasonable. The only thing that bothered him was a doubt that he could make that reasonableness clear to Spade. He had never told anybody his story before, and thus had not had to attempt to make its reasonableness explicit. He tried now.

“I got it all right,” Spade told Brigid O’Shaughnessy, “but Mrs. Flitcraft never did. She thought it was silly. Maybe it was. Anyway it came out all right. She didn’t want any scandal, and, after the trick he had played on her – the way she looked at it – she didn’t want him. So they were divorced on the quiet and everything was swell all around.

“Here’s what happened to him. Going to lunch he passed an office-building that was being put up – just the skeleton. A beam or something fell eight or ten stories down and smacked the sidewalk alongside him. It brushed pretty close to him, but didn’t touch him, though a piece of the sidewalk was chipped off and flew up and hit his cheek. It only took a piece of skin off, but he still had the scar when I saw him. He rubbed it with his finger – well, affectionately – when he told me about it. He was scared stiff of course, he said, but he was more shocked than really frightened. He felt like somebody had taken the lid off life and let him look at the works.”

Flitcraft had been a good citizen and a good husband and father, not by any outer compulsion, but simply because he was a man most comfortable in step with his surroundings. He had been raised that way. The people he knew were like that. The life he knew was a clean orderly sane responsible affair. Now a falling beam had shown him that life was fundamentally none of these things. He, the good citizen-husband-father, could be wiped out between office and restaurant by the accident of a falling beam. He knew then that men died at haphazard like that, and lived only while blind chance spared them.

It was not, primarily, the injustice of it that disturbed him: he accepted that after the first shock. What disturbed him was the discovery that in sensibly ordering his affairs he had got out of step, and not in step, with life. He said he knew before he had gone twenty feet from the fallen beam that he would never know peace until he had adjusted himself to this new glimpse of life. By the time he had eaten his luncheon he had found his means of adjustment. Life could be ended for him at random by a falling beam: he would change his life at random by simply going away. He loved his family, he said, as much as he supposed was usual, but he knew he was leaving them adequately provided for, and his love for them was not of the sort that would make absence painful.

He went to Seattle that afternoon,” Spade said,

“and from there by boat to San Francisco.

For a couple of years he wandered around and then drifted back to the Northwest, and settled in Spokane and got married.

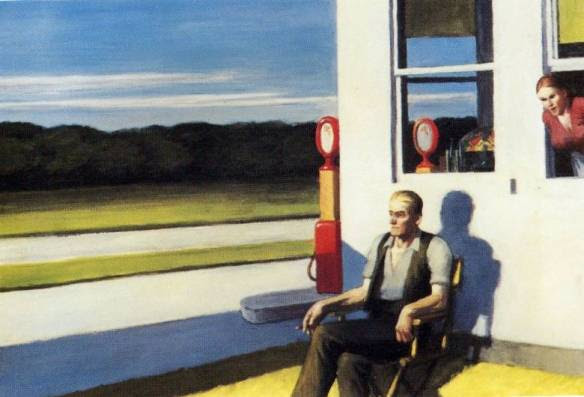

His second wife didn’t look like the first, but they were more alike than they were different. You know, the kind of women that play fair games of golf and bridge and like new salad-recipes. He wasn’t sorry for what he had done. It seemed reasonable enough to him. I don’t think he even knew he had settled back naturally in the same groove he had jumped out of in Tacoma. But that the part of it I always liked. He adjusted himself to beams falling, and then no more of them fell, and he adjusted himself to them not falling.”

AFTERWORD

Here’s what I’ve just philosoflickly argued.

(1) Whether in the 1920s or the 2010s, according to the worldview of capitalist bosses and their political collaborators, we’re nothing but decision-theoretic, economic animals.

(2) Whether in the 1920s or the 2010s, according to the worldview of philosophical scientism and mechanism, we’re nothing but natural automata. (The Vienna Circle’s “scientific conception of the world.”)

(3) Therefore, according to the composite worldview provided by capitalist bosses, their political collaborators, natural scientists, and naturalistic philosophers, whether in the 1920s or the 2010s, we’re nothing but decision-theoretic, economic automata.

(4) And to the extent that we accept this composite worldview, subtly or not-so-subtly imposed on us by means of the cradle-to-adulthood educational system, political training, ideologically-biased technology, and the compliant, ideologically-biased media that universally surround us, we’re all-too-easily manipulated into becoming ideologically hyper-obedient neoliberal professionals, the Portlandia vanguard of the oppressed.

(5) But actually, we’re all free agents, rational animals with innate human dignity, and a fundamental need to create and lead meaningful, morally principled lives.

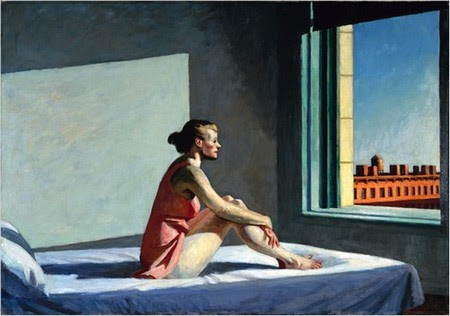

(6) The conjunction of (4) and (5) produces intense cognitive dissonance, anxiety, and anomie. (Eliot’s “hollow men.”)

(7) Therefore, above all, we need to break out of this essentially dehumanizing, existentially absurd, “self-incurred immaturity,” revolutionize our hearts and liberate our minds from this mental slavery, act autonomously, and realize the categorical norms of our rational humanity, individually and collectively.

(8) But even supposing that we do try our damnedest to break out of all this shit, it’s all-too-easy to slide unwittingly back into the half-hearted, mind-enslaving trap laid for us by our smiley-faced oppressors. (Hammett’s “Flitcraft parable.”)

Against Professional Philosophy is a sub-project of the online mega-project Philosophy Without Borders, which is home-based on Patreon here.

Please consider becoming a patron!