The fate of philosophy in the Anglo-American world in the twentieth century was to forget the lessons of history and to bind itself (largely thanks to the analytic school of thought) to a universalistic and objectivist project that was hopelessly flawed from the very start. The sad result of philosophy’s adherence to this project was the professionalization of philosophy in universities, a professionalization that has significantly tied the discipline to corporatist (in John Ralston Saul’s use of the term) interests that have served to denude philosophy of a vital, critical role as the center of social, political, and cultural debate and critique.1

Early in the twentieth century, notably in Germany, there was much talk about the “crisis of historicism.” Indeed, one of Ernst Troeltsch’s best-known works was entitled Der Krisis des Historismus. Others, like Friedrich Meinecke and Karl Mannheim, took up the challenge asserted by Marx’s historical materialism and Nietzsche’s genealogy of morals, trying to come to grips with this crisis. In essence, the “crisis” consisted of the notion that, contrary to the findings of the philosophical canon up until the mid-19th century, our great metaphysical, moral and political beliefs and values change with time and place: there were no important universal human truths that the philosopher could aspire to learn and propagate to future generations of thinkers. As R. G. Collingwood, the underrated archeologist, historian, and philosopher asserted while discussing Hume, the Enlightenment notion of a “science of human nature” had become impossible in the wake of this crisis. There were human natures, shifting constellations of presuppositions (to use Collingwood’s terminology), but no absolute metaphysical or moral structures that the great thinker could intuit and lay out in a learned treatise.

Karl Popper, one of the great masters of contemporary scientific empiricism, took on the historicists in his great muddle The Poverty of Historicism. The book is a muddle because Popper, in his characterization of the phenomenon, mixes together elements that are truly historicist – the idea of the “historical relativity of social laws”2 and the general importance of historical categories – with anti-historicist or quasi-historicist elements like holism, grand laws of historical development and historical prophecy. But leaving aside these exegetical niceties, Popper knew enough to know that historicism was trouble – it called into question objectivism in the sciences (including sociology, which is the ostensible focus of his book), a questioning that his book was dedicated to squashing.3

The Continental tradition in philosophy had no great problem with this crisis. In fact, existential ethics, as found in Sartre’s philosophical works, Camus’s novels and elsewhere, explicitly acknowledged it in accepting that there were no objective values out there in the world for the thinker to discover. Witness the sublime clarity achieved by Camus’s Meursault as he awaits his death in prison:

As if this great outburst of anger had purged all my ills, killed all my hopes, I looked up at the mass of signs and stars in the night sky and laid myself open for the first time to the benign indifference of the world. And finding it so much like myself, in fact so fraternal, I realized that I’d been happy, and that I was still happy.4

Indeed, Kierkegaard’s century-old (by Sartre and Camus’s day) leap of faith showed the way: we choose our basic presuppositions, our life values, by non-rational leaps into the unknown. This notion that our core philosophical foundations cannot themselves be grounded in reason or experience emerged from time to time both within and without Continental thought in the last century: Collingwood, in his An Essay on Metaphysics (1942), claimed that our foundational scientific and metaphysical ideas were “absolute presuppositions,” from which we derived empirically testable relative presuppositions (e.g. scientific laws like Newton’s f=ma); Thomas Kuhn famously argued that “normal science” operates within scientific paradigms that define what counts as good research, and that these paradigms, once burdened with too many anomalous experimental results, undergo periodic revolutions; while Michel Foucault tried to show in The Order of Things (1966) – which he subtitled “An Archaeology of the Human Sciences” – that human sciences such as linguistics, biology, and economics themselves are at the mercy of meta-theoretical categories, categories that underwent a fundamental shift between the Renaissance and the Enlightenment.

Later, in the second wave of Continental thought (from the late 1960s on), which we could roughly characterize as “post-structuralist” or “post-modernist”, the crisis of historicism was heartily embraced. Later in his career, Foucault made explicit the relationships between power and knowledge in discourses about madness and the asylum, the medical clinic, schools, prisons, and sexuality, all of which changed over time as power relationships shifted; Jacques Derrida laid to rest once and for all any notion of the eternality of the relationship between signifier and signified in the sentence, condemning linguistic meaning to Heraclitus’s ever-flowing river; while Jean Baudrillard pointed out how our image-obsessed, media culture causes us to live in the Third Order of the Simulacra (beautifully portrayed in the 1999 film The Matrix), where the Real has become a product of media spin and television narratives. Some of these ideas have even washed up on the shores of the New World. The American thinker Richard Rorty, himself an ex-analytic philosopher who betrayed his old comrades by embracing elements of Continental and postmodern thought (and earned their resentment for doing so), argues that the truth is made and not found. It is not “out there”, in the world, but is purely a product of human linguistic descriptions. Since this is the case, he argues that we can only hold on to our values ironically, knowing that there’s nothing in the structure of reality that guarantees their validity.

However, most of this has been ignored, or treated with scorn, by Anglo-American philosophers teaching in North American universities. A much stronger force than the intellectual dust storm caused by historicism and postmodernism has impacted upon the development of philosophy in the 20th century, namely, techno-corporatism. The two chief social developments of the 20th century can be seen as (a) the amazing development of technology in the century, from the Wright brother’s flimsy biplane and Marconi’s static-laden wireless to Mach 3 jet fighters and mass- produced cell phones; and (b) the degree to which pretty well all of us serve large, bureaucratic, corporate structures, under the reign of which we are all, to varying degrees, prisoners in Max Weber’s iron cage of rationality. All of this is linked, of course, to the equally amazing success of late or global capitalism over the last hundred years. It would indeed be surprising if these forces–technological development, bureaucracy, globalized capitalism, and corporatism–didn’t have a profound effect on the career of philosophy.

What was this effect? Academic philosophy was forced slowly but surely into this iron cage of techno-rationality in the Anglo-American world as its core method of inquiry became more and more that of logical and linguistic analysis. This method is premised on a strict scientific empiricism. From Bertrand Russell and A.J. Ayer to Willard Quine, Donald Davidson and Hilary Putnam, professional philosophy in the Atlantic world chose to redefine truth and meaning as the outcome of a close analysis of ordinary language or of logical computation.5

Speaking of Ayer, Gilbert Ryle, and others, Peter Winch traces the analytic approach’s pedigree back to Locke’s “under-labourer” view of the philosopher. The under-labourer’s job is to clear away the rubbish that blocks our way to knowledge. Just as “a garage mechanic is concerned with removing such things as blockages to carburettors, a philosopher removes contradictions from the realm of discourse.”6 Linguistic analysis is thus the under-labourer’s basic tool. The sort of knowledge whose advance is being blocked by all that philosophical rubbish is, of course, physical science.

All of this served corporatist interests quite nicely. Mulling over Nietzsche’s concept of the Will to Power, or looking for meaning in Sartre’s existential void, are of little use to engineers, physical scientists, business managers, or bureaucrats. Instead, the contemporary university has enshrined the analytic or computational approach to philosophical inquiry to serve the needs of a technological and rational-bureaucratic society. As J. F. Lyotard suggested in his 1979 report to the Quebec government The Postmodern Condition, our era is dominated by “performativity” as its central rationale for research. This sets up an equation of riches, power, and truth. If the state and private corporations are to pour money into our universities, the research that they produce must “pay off” in useful knowledge.

Specifically, we can find evidence of the alliance of the analytic or computational approach with corporatist interests in the following trends found in Philosophy departments:

(1) We see it in the importance of formal logic in most philosophy curricula – added to the cultural capital that adheres to the formal logician within most philosophy departments. It is common knowledge that formal logic cannot generate new truths, but merely analyzes what’s already there. This seems to be built into the very nature of the beast. In other words, formal logic is an analytic device, not a truth-generating language. The advantage of symbolic logic to the analytic school of thought is that philosophical terms and ideas must first be stripped of their evocative and ambiguous qualities before being plugged into a syllogism. This gives philosophy a patina of respectability in the life-worlds of mathematics and science, and thereby both justifies the discipline’s existence to money-granting bodies, while carving out a field of research –logical analysis–that is both “scientific” and specific to the discipline. Unfortunately, it also means that the logician can say very little of interest to non-logicians, never mind non-professional philosophers. To do their work, they must adopt perhaps the most arcane dialect of all (as Saul accuses professional philosophers in general of doing), that of formal symbols drained of real-world significance.

(2) We also see it in the more recent popularity of critical thinking, reasoning skills, and informal logic courses and research. The point of this is obvious: realizing that formal logics are of little use in sorting out real-world problems, e.g., analysing the media, political propaganda, cafeteria truth claims, bar-room ethical debates, etc., analytic philosophers have invented a new sub-discipline in order to colonize the world of the everyday with logical rigour. It’s not in the least surprising that by the end of the century such courses were amongst the most promoted in North American philosophy course offerings: unlike formal logic, which reduces everyday language to empty symbols, critical thinking leaves much of this language intact, choosing instead to wag fingers of judgement at the fallacious reasoning contained within it. Ironically, drilling the names of fallacies into undergraduates usually has little effect on their long-term reasoning skills, while those poor souls saddled with teaching such courses (usually graduate students or part-time contract teachers) often rate it lowest on their wish lists of future teaching choices. Further, when it comes to making decisions within the academy, critical thinkers (in my experience) fare no better than people with a firm grip on common sense in avoiding such dreaded enemies as guilt by association, ad hominems, or tu quoques.

Once again, this development gives academic philosophy a patina of utilitarian respectability: it may not be able to discover new sub-atomic particles, help you join the corporate elite, or build a better bicycle; but it can help you reason better, regardless of what you choose to reason about. In other words, reasoning is no longer an embodied, authentic attempt to understand politics, culture, morality, or (the) human understanding, but a plug-in module that can be applied (a pregnant philosophical prefix at the end of the century) to any thing one chooses to reason about – whether it’s the most sublime metaphysics, or arguments over the price of bananas.

(3) Thirdly, we can see broad evidence of the growing power of corporatist interests in the general popularity of “applied” philosophy – in some forms of applied ethics (more on this in a minute), in critical thinking (as I’ve just shown), and in philosophies “of”: the philosophy of law, the philosophy of science, the philosophy of medicine, and so on. Once again, a large portion of the curriculum is being redefined as a collection of plug-in modules whose purpose is to serve professional corporate interests: lawyers, accountants, doctors, dentists, optometrists, etc. Philosophy, to advance its cause within the corporate structures of the university, has chosen to sign away its once proud independence in exchange for a steady intake of lucre. It no longer emulates Socrates’s gadfly, but Aristotle’s tutoring of Alexander – less interested in questioning and goading the powerful and wealthy, it instead serves its students a few quickly forgotten scraps from the grand canon.

(4) More specifically, we can find evidence of this techno-corporatism in the recent popularity of certain narrowly construed types of applied ethics. This is the most significant area of the movement toward applied philosophies in academe. We see business ethics, environmental ethics and bio-medical ethics courses full of undergraduate students who have no intention of exploring the philosophical canon in any greater depth once the term has ended. Indeed, in many cases, philosophy departments have negotiated deals with professional faculties whereby students in the latter are compelled to take the applied ethics courses offered by the former. Sadly, students taking these courses often resent this, or come to these courses (notably to business ethics courses) with a corporatist ideology already firmly in place. Thus applied ethics takes on the form of wrist-slapping exercises: “yes, NASA was wrong to launch the Challenger with faulty O-rings”; “oh my, Ford executives were morally culpable in allowing the Pinto to be produced when they knew it would blow up if struck firmly from behind”; etc., etc. Advocates of applied ethics get the sense that by engaging in such wrist-slapping they’ve fought the good fight, and send their students out into the corporate and bureaucratic worlds with the comforting sense that they’ve imbibed a few drams of ethical restraint amidst the gallons of self-interest served to them by their native disciplines.7 Once again, these courses become plug-in modules serving the interests of professional schools that have little if any interest in philosophical speculation. They were window dressing for philosophy departments fighting for their existence against cuts to university programs.

(5) And lastly, we can see these forces at play in the continuing significance of a logico- positivist methodology in epistemology and metaphysics, and to a lesser degree in ethics and political theory. In the philosophy of mind we see this in both the continuing dominance of physicalist reductionism (e.g., Daniel Dennett’s Consciousness Explained) and in the new vogue for cognitive science, which seeks to explain mental activity along the lines of computer algorithms and models. Another case in point is the popularity of game theoretic models for ethical and political reasoning, models that see the Prisoner’s Dilemma as their Rosetta Stone for solving puzzling moral dilemmas. This is true despite the fact that anyone who sat around do game theoretic analyses before making important moral decisions would appear to the uninitiated as a farcical character akin to Dickens’s Mr. Gradgrind, who ground out his decisions by running a heap of facts through his marvellous felicity-calculating engine.

Carlyle had it right in the 1830s, when he condemned his own age as one of machinery.

His words are a pregnant prophecy of the state of things a century and half later:

Were we required to characterise this age of ours by any single epithet, we should be tempted to call it, not an Historical, Devotional, Philosophical, or Moral Age, but, above all others, the Mechanical Age. It is the Age of Machinery, in every outward and inward sense of that word; the age which, with its whole undivided might, forwards, teaches, and practices the great art of adapting means to ends. Nothing is now done directly, or by hand; all is by rule and calculated contrivance…Men are grown mechanical in head and heart, as well as in hand…Their whole efforts, attachments, opinions, turn on mechanism, and are of a mechanical character. (Thomas Carlyle, “Signs of the Times”)

Little did he know that much of the literature, thought, art, architecture, and music of his own age would vastly eclipse in its organic richness that of the barren modernism of the past century.

Compare the neo-Gothicism of the British Houses of Parliament and the Pre-Raphaelite paintings of Rosetti and Waterhouse to the sterile black boxes of Mises Van der Rohe and the abstract expressionism of Malevich or Mondrian. The visionary gleam largely disappeared from 20th century art, functionality and the machine aesthetic coming to dominate it under the banner of modernism (at least until the postmodernism of the 1980s and later). Anglo-American philosophy followed suit, worshipping linguistic clarity at the cost of moral or aesthetic richness, the functional beauty of logical deduction over the fuzziness of literature, the sublime productivity of the computer as a model for the human mind over the slimy morass of that which emerges from a study of our basic drives and of existential meaning.

In short, the fate of philosophy in the Anglo-American world in the 20th century is to move away from substantive questions of meaning, truth, morality, and politics, and toward logical and linguistic analysis, tied to a plug-in module approach to interpreting the moral world. This fate is tied to a forgetting of the lessons of history–or, perhaps speaking more accurately, to a refusal to take history seriously at all. The truths of philosophy are not seen as flowing from period to period or from place to place, riding along Heraclitus’s river. Instead, they sit tantalizingly enclosed in Parmenides’s sphere, always just beyond the reach of the grasping minds of analytical scientism.

Let me finish with a simple question: why is it that in no Philosophy department in Canada are the important Canadian thinkers of the 20th century – Harold Innis, George Grant,

Marshall McLuhan, and their living heirs – regularly taught as a independent school thought, if at all? This can in part by explained by the simple fact that these departments are dominated by our American and British cultural colonizers who, in each case, look outside our borders for their philosophical exemplars. But I would suggest that there is a more fundamental explanation of this curious phenomenon: that these thinkers observed that the way we think, the way we communicate, and the way we live are all tied to the media and technologies that serve our thinking, communicating, and living. In other words, logical and linguistic analysis cannot produce universal or objective truths – as McLuhan probed us to consider, new media and technologies alter our basic sense ratios, our way of perceiving the world. Culture counts. And since cultures change, history counts. Yet historicism could not be tolerated by an analytic hegemony fuelled by techno-corporatism – hence, it attempts to silence its voice.8 So the lessons of history, the chief of which is the fact that our basic values and ideas are always in flux, were forgotten by professional philosophers. Such was the fate of philosophy in the 20th century.

NOTES

1 Saul defines corporatism as “the persistent rival school of representative government. In the place of the democratic idea of individual citizens who vote, confer legitimacy and participate to the best of their ability, individuals in the corporatist state are reduced to the role of secondary participants. They belong to their professional or expert groups – their corporations – and the state is run by ongoing negotiations between those various interests. This is the natural way of organizing things in a civilization based on expertise and devoted to the exercise of power through bureaucratic structures.” The Doubter’s Companion (Toronto: Penguin, 1995), 74. See his Massey Lectures from 1995, The Unconscious Civilization (Concord: Anansi, 1995), for a lively critique of corporatism.

2 See Karl Popper, The Poverty of Historicism (London: Routledge, 1961), 6.

3 A couple of decades after Popper’s Poverty first appeared, Thomas Kuhn made clear the historicist basis of even the physical sciences – his The Structure of Scientific Revolutions shows how the gaps between “normal science” are bridged by scientific revolutions, paradigm shifts that redefine what “counts” as valid research. His philosophy of science denies the validity of what he terms “the ontological march to truth.”

4 Albert Camus, The Outsider, trans. Joseph Laredo (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982), 116.

5 Although I should point out that there have always been strong counter-movements to the analytic mainstream–movements that are, perhaps, more popular amongst students of philosophy than their teachers. Existentialism, phenomenology, idealism, postmodernism, cultural analysis, literary criticism, etc., are cases in point. However, even as late as 2012, it is quite clear that analytic philosophy has successfully maintained its position of ideological hegemony in Philosophy departments throughout the English-speaking world.

6 Peter Winch, The Idea of a Social Science and its Relation to Philosophy (London: Routledge, 1958), 3-5.

7 This should be intuitively true to anyone who has ever tried to teach ethics to business students, or heard the sad tales of law students ripping out case studies from legal texts, or stealing books from the campus library, to handicap their classmates’ chances on assignments and exams. The March 2001 scandal of large numbers of University of Toronto law students lying about their test scores to prospective employers is only one case amongst many that point to how the plug-in module approach to moral life doesn’t work. On a much lower moral plane we find the recent spate of school shootings in the US–from Columbine in 1999 to Virginia Tech in August 2007 and Northern Illinois University in 2008–though their relation to the professionalization of ethics is less clear.

8 Oddly, the darker twin of historicism, moral relativism, doesn’t seem to be as much of a problem to techno-corporatism in the technological and economic spheres: after all, whether a piece of technology works well, or whether a given product can be efficiently manufactured, advertised, and sold to the consuming masses is what counts, and not the morality of these processes.

Things are different, however, in the intellectual sphere. When professional philosophers come to actually doing ethics as a professional activity, most of them turn out to be either contract/game theorists, who believe that moral decisions can be made by quantifying possible outcomes, or at least by generalizing about the most rational decision to make given an analysis of the actor’s starting position; or Kantians, perhaps attracted by Kant’s close argumentation, logical rigour, and ponderous professorial self- certainty. In either case, they are objectivists, seemingly oblivious to Hume’s, Nietzsche’s, Mackie’s, and other sceptical critiques of objective views of ethics. It would be difficult to teach ethics in the modern university from an subjectivist, egoist, or moral relativist starting point.

APP EDITORS’ NOTE: This is the fifth in a six-part series featuring the work of Doug Mann.

Here is the original publication information for this article:

Mann, D. (2012) “Forgetting the Lessons of History: The Fate of Philosophy in the 20th Century,” Canadian Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 3, 73-78.

Like Marc Champagne’s essay, “We, the Professional Sages: Analytic Philosophy’s Arrogation of Argument,” Mann’s work in the 00s and early 10s of the 21st century remarkably anticipates many ideas and themes developed and explored by APP since 2013.

More information about Doug Mann’s work can be found HERE.

![]()

Against Professional Philosophy is a sub-project of the online mega-project Philosophy Without Borders, which is home-based on Patreon here.

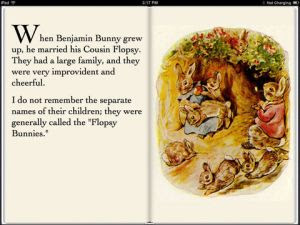

Please consider becoming a patron! We’re improvident, but cheerful.